Warning of six more years of austerity, the Chancellor’s package of measures included a number of provisions that, on the Treasury’s predictions, are likely to increase the numbers of children in poverty.

Key points in the statement include:

- An expansion of free childcare places for two-year-olds from the poorest 20 per cent of families to the poorest 40 per cent.

- Although some benefits such as the state pension and jobseeker’s allowance were increased in line with the CPI inflation measure (5.2 per cent), the basic, lone parent and child element of working tax credit was frozen, saving £1.2bn a year, money that was to be used to pay for public building projects, a cap on rail fare rises and a fuel duty freeze. The Treasury accepted that with inflation running at more than 5 per cent a year, this was likely to increase the number of children in poverty by up to 100,000. This made it more unlikely that the government would meet the legally binding target set out in Labour’s 2010 Child Poverty Act for the government to end child poverty by 2020. The measure would also erode the incentive to get a job for those facing low-paid work.

- Tax credits, which have never been popular with the Conservatives, are due to be superseded by Iain Duncan Smith’s universal credit in 2013.

- A further two-year pay freeze for public sector workers on top of the two-year freeze announced in June 2010.

- Bringing forward the date of the pension age rise to 67 to April 2028 instead of 2036, affecting 8 million workers aged between 42 and 51.

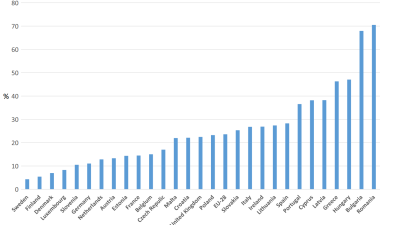

- The overall impact according to the Treasury’s own charts (chart 1B of the supplementary document, Distributional Analysis) will be that the bottom decile of the income distribution will suffer the second largest proportional losses from all the tax, tax credit and benefit measures carried out by the Coalition government or carried over from the previous Labour government. The measures will be regressive across the bottom four deciles. The biggest losses according to these charts would be in the richest decile.

In a heated exchange in the Commons between David Cameron and Ed Miliband, Cameron insisted that the budget was ‘fair’ because the Treasury’s distributional analysis showed that the richest 10 per cent would be the hardest hit. Miliband insisted that this analysis was wrong because the Treasury figures included not just an account of the impact of the mini-budget – it also included some measures passed by Gordon Brown. Miliband quoted figures produced by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), which showed that the impact of the mini-budget package alone was more regressive than suggested by the Treasury, with the poor bearing bigger proportionate cuts than the rich. The IFS analysis suggested that the bottom 30 per cent would lose and the top 60 per cent gain.

Robert Joyce, the IFS economist who compiled the table, was asked by The Guardian which were the fairest figures to use. Joyce said that the figures cited by both sides are factually correct; which set you choose to use just depends on whether you want to assess the impact of the new changes in 2012–13 (as Miliband does) or the accumulated changes up to that point (as Cameron argued was fairer to do). He added ‘Regardless of which stats you use, the things that are driving the large losses for the top group in the Treasury’s analysis are mostly things that were announced by Labour they came in during the coalition’s reign. If you’re specifically interested in measuring the coalition’s policies, you don’t want to be accounting for that.’

The full Autumn statement is available at the Treasury website.

The IFS analysis is available at the Institute for Fiscal Studies website.

The comments from Robert Joyce are available at The Guardian website.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.