Work in itself is not a solution to poverty, in part because of the spread of low pay work over the last 30 years, argues Richard Dickens in the latest National Institute Economic Review (vol. 218, no. 1). In his article, ‘Child poverty in Britain: past lessons and future prospects’, Dickens examines the impact on child poverty of changes over the past decade in wages and work, tax and benefits, and demographics. He finds that benefit reform increased work among families with children but this did not translate into large falls in child poverty – those entering work depended on substantial increases in benefits to lift them over the poverty line. Changes in the wage structure and demographics increased poverty, while changes to benefits (and, to a lesser extent, taxes) over that period had reduced poverty by making the tax/benefit system more progressive and by favouring families with children over those without children.

Dickens quotes a study by John Hills (‘The Blair Government and child poverty: an extra one percent for Children in the United Kingdom’ in I. Sawhill (ed.), One Percent for the Kids, Washington DC, Brookings Institute, 2003), which found that by 2003 families with children were £1,200 a year better off than in 1997 in terms of taxes and benefits, a policy that cost £9bn or 1 per cent of GDP.

The paper supports other evidence that the interaction of the benefits system with a high level of workless households and high wage inequality leads to poor work incentives for those considering entering work. This is particularly so for single parents and those with children who would be unlikely to be much better off in work than on benefits. Thus, while active labour market policies increased the lone parent employment rate by about 10 percentage points – reversing the previous long-term downward trend – the impact on child poverty was limited.

Dickens concludes that the policies of the Coalition government are likely to result in a substantial increase in poverty because the government continues to emphasise the importance of getting workless households into work while cutting benefits that will disproportionately affect poor households. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has come to a similar conclusion (see ‘Low income households depend more on external support’) and the Resolution Foundation Report, Better Off Working?, has found that many working families experience financial strain.

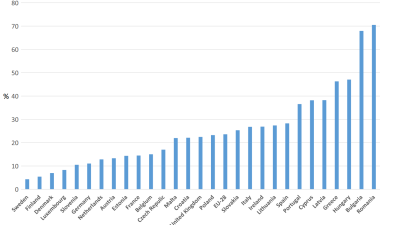

What Dickens’s study confirms is that work itself is not a solution to poverty, in part because of the spread of low pay work over the last 30 years. Over that time the proportion of those in low paid work has doubled to around 22 per cent (see S. Lansley, The Cost of Inequality, Gibson Square, 2011, p.75).

The drivers of earnings inequality

The same issue of the National Institute Economic Review (vol. 218, no. 1) contains three further research articles on poverty and inequality: Jonathan Portes, ‘An introduction’; Mark B. Stewart, ‘The changing picture of earnings inequality in Britain and the role of regional and sectoral differences’ and Stephen P. Jenkins, ‘Has the instability of personal incomes been increasing?’.

In ‘The changing picture of earnings inequality in Britain and the role of regional and sectoral differences’, Mark Stewart finds that the growth in earnings inequality in the UK from 1970 to 2010 has been driven primarily by London and the financial sector. Changes in inequality outside London and in non-financial sectors have been small. This appears to raise a question over the mainstream explanations for rising wage inequality since the early 1980s – that it has been a product of globalisation and technical change.

In ‘Has the instability of personal incomes been increasing?’, Stephen Jenkins finds that, in contrast with the USA, in the UK there was no significant increase in income instability (as measured by real net equivalent household income) between the early 1990s and the mid-2000s. One possible explanation is that the benefits safety net in the UK is more developed and better able to compensate for changes in labour incomes than in the USA.

While Jonathan Portes notes in ‘An introduction’ to the research articles, that in relation to the debate in the USA inequality at a moment in time is less of a problem if there is substantial income mobility through time. On the future, Portes concludes that:

the prospect is that income inequality is likely to rise again, driven by structural change and government policies

and that:

increases in static inequality measures are not offset by greater income mobility or intragenerational social mobility.

The full articles can be read in the National Institute Economic Review (2011, vol. 218, no. 1), R1 – R43 (subscription only).

Jonathan Portes, ‘An introduction’

Richard Dickens, ‘Child poverty in Britain: past lessons and future prospects’

Stephen P. Jenkins, ‘Has the instability of personal incomes been increasing?’

Mark B. Stewart, ‘The changing picture of earnings inequality in Britain and the role of regional and sectoral differences’

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.