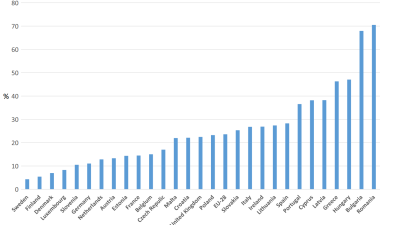

The gap between rich and poor countries and within traditionally more equal countries has been rising, finds the latest OECD report, Divided We Stand, Why Inequality Keeps Rising. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report found that:

- The gap between rich and poor in OECD countries has reached its highest level for over 30 years.

- The income gap has risen even in traditionally egalitarian countries, such as Germany, Denmark and Sweden, from 5 to 1 in the 1980s to 6 to 1 today. The gap is 10 to 1 in Italy, Japan, Korea and the United Kingdom, and higher still, at 14 to 1 in Israel, Turkey and the USA. In Chile and Mexico, the incomes of the richest are still more than 25 times those of the poorest, the highest in the OECD, but have finally started dropping. Income inequality is much higher in some major emerging economies outside the OECD area. At 50 to 1, Brazil’s income gap remains much higher than in many other countries, although it has been falling significantly over the past decade.

- The pay gap between the highest and lowest earners in the UK has grown more quickly than in any other high-income country since 1975. Data showed the money earned by the country’s top 1 per cent of earners doubled from 7.1 per cent of the total UK income in 1970 to 14.3 per cent in 2005.

- Just prior to the global recession, the top 0.1 per cent of top earners accounted for 5 per cent of total pre-tax income.

Launching the report in Paris, OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría said, ‘The social contract is starting to unravel in many countries. This study dispels the assumptions that the benefits of economic growth will automatically trickle down to the disadvantaged and that greater inequality fosters greater social mobility. Without a comprehensive strategy for inclusive growth, inequality will continue to rise.’

The main driver behind rising income gaps has been greater inequality in wages and salaries, as the high skilled have benefited more from technological progress than the low skilled. Reforms to boost competition and to make labour markets more adaptable, for example by promoting part-time work or more flexible hours, have promoted productivity and brought more people into work, especially women and low-paid workers. But the rise in part-time and low-paid work also extended the wage gap.

Tax and benefit systems play a major role in reducing market-driven inequality but have become less effective at redistributing income since the mid-1990s. The main reason lies on the benefits side: benefits levels fell in nearly all OECD countries, eligibility rules were tightened to contain spending on social protection, and transfers to the poorest failed to keep pace with earnings growth. As a result, the benefit system in most countries has become less effective in reducing inequalities over the past 15 years. Another factor has been a cut in top tax rates for high-earners.

‘There is nothing inevitable about high and growing inequalities,’ said Mr Gurría. ‘Our report clearly indicates that upskilling of the workforce is by far the most powerful instrument to counter rising income inequality. The investment in people must begin in early childhood and be followed through into formal education and work.’

The OECD called for governments to review their tax systems to ensure that wealthier individuals contribute their fair share of the tax burden. This can be achieved by raising marginal tax rates on the rich but also improving tax compliance, eliminating tax deductions, and reassessing the role of taxes in all forms of property and wealth.

The full report is available on the OECD website, where underlying data on income inequality can be viewed in Excel.

See also:

The detailed country note on the UK, where you will also be able to view the underlying data in Excel.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.